Archive

End-Game Primacy: Part 3

Part 3: Squaring the Circle

If you’re reading this you probably either came straight from the Introduction or were patient enough to work through Part 1 and Part 2. For simplicity, here is the short form of my theory on the ideal MMO content:

End-game primacy is the idea that the bulk of any MMO development time needs to be spent on maximizing end-game content and that this goal is best achieved by embracing complex systems driven by player interaction, rather than static content. Or put a different way: an MMO’s real story begins after the scripted story ends.

As I discussed in part 2, complex systems can be consumed by players longer than static content, but they are also significantly harder to create well. What works in a single player game may not work in an MMO, and vice versa. It is a lot easier to account for a few players’ actions than it is to predict the impact of millions. Millions of players is millions of opportunities to undo any work developers put into the game. Structured static content offers a lot more control for developers. Instancing, phasing, personal stories, and other tools isolate players from the larger game population, while simultaneously making it easier to tell a story to the player. It lets developers preserve the narrative format of single-player games. In contrast, unstructured simulations take control away from a development team. The simulation elements are built into the game world and then left to the players’ whims on what to do with them. This is a frightening prospect because systems not designed to scale particularly well can tend to spiral well out of control, at the detriment of other aspects of the game. For instance, if players can build structures on game landscape, the game world will almost definitely end up suburban. If players can build in a particular spot, they will if for no other reason than they can. Expecting that it would not happen is betting against the odds.

Qualities of Good End-Game Content:

End-game content systems needs to ebb and flow organically, self-regulating through internal feedback mechanisms. In the above example of players building on the terrain, physical game space is limited while the numbers of players who can (and will) build houses has no theoretical limit. Instancing off the construction projects or expanding the physical land mass using some kind of terrain generator are two ways you can address the finite space. I’m not stupid enough to think that the second of those two options is exactly feasible. In many cases, it may be impossible. The alternative of instancing off construction projects or imposing artificial limits on where players can build to control the urban boom misses the point of building a game with lots of players in the first place. To make the system work, there needs to be a natural feedback mechanism in place. For housing, if players can create them – they must also be able to destroy them. Determining the ratio between building and destroying would require a fair amount of find tuning, however. If it’s hard too build and easy too destroy, no one will bother building. On the other hand, if it is to easy to build and to hard to destroy, you still end up with a sprawl.

Going back to Part 2, auction houses have natural self-regulation through the invisible hand of supply / demand, but they lack a mechanism to contribute to player narrative. Systems that have ways to report activity and interactions back out to players are another hallmark of a good end-game system. Players can buy and trade all day on the auction house, but if there is no mechanism to report major fluctuation in trade, players will likely feel isolated in their game experience. Even if such a mechanism exists, it probably does not tie into other systems. Ideally, if a market change occurs, it should be in response to in-game events. Knowledge of these events provides players immersion, rather than just leaving them staring at a user interface spreadsheet tracking their purchases. A good end-game content system will let developers track and aggregate player interactions within and across systems to facilitate narrative development. In the housing example above, a mechanism to monitor and encourage players to cluster buildings together facilitates the construction of towns instead of haphazard sprawl. For instance, perhaps building in close proximity to one another increases their natural defense. Two houses have the defense of three; three the defense of five; and so on. A shack in the woods could be torn down in a few minutes, where several dozen buildings together takes over a day. Several towns merge to form a city which takes a week to siege. And each of these units (e.g. town, city) provides an entity that developers can track and use as a piece to a personal player narrative that is not separate from all other player narratives.

An Opportunity in Player Social Landscape:

These are simplistic examples, to be sure, but it gets to the point of what I’m trying to explain. I cannot suggest an end-game system that will work in every MMO. Each game has its own limitations based on engine, design philosophy, resources and a host of other factors. However, there is one area in many MMOs today that I believe remains underdeveloped, but which also has great potential to add depth to end-game experience and help developers create quality evolving narratives in the process. While most developers spend plenty of time shaping their landscapes and dungeons and are loathe to let players ruin that art, social terrain is an area that does not currently have structure and therefore cannot be destroyed.

The fact that I can often only be the member of one guild and my relationships to other players are defined as “friend” or “not friend” is fairly simplistic. This flat and binary social structure is surprising given that large numbers of players are a feature of MMOs. Certainly, social terrain is difficult to communicate meaningfully – even Facebook struggles with it – but games need more than a few binary associations to link players. In life, we play many roles and in games we do as well. Is there a particular reason that a player can and should only belong to one guild in a game? I would argue no. Further, guilds are generally the only mechanism to permanently join players in games. This is an artificiality that misses the point. Letting players create different kinds of associations among themselves and build on the quality of those relationships through game play would be a fantastic way to add depth to a relatively one dimensional system.

Imagine if player organizations came in many different forms, which were not binding to individual players. Guilds might still exist as the highest form of player grouping, offering resources like shared banks and chat channels. Others might exist for circles of friends to communicate. These circles could extend between guilds and offer benefits like being able to travel immediately to your friends’ location. Still others might exist for trade groups: players who regularly share crafting resources to each others’ benefit. Being a member of this group may offer additional crafting benefits. Player organizations like this only come into existence when the game recognizes a cluster of individual player associations strong enough to warrant it. When players “friend” one another they select the kind of relationship they want to build. Small groups of friendship-linked players might warrant a “friend circle,” clusters of adventuring-linked players might warrant a “guild circle,” and clusters of trade-linked players might warrant a “trade circle,” and so on.

These interlocking social circles would create an inherently organic system that already lies on top of almost any game’s existing game play. Anchoring these circles into less organic game systems could vastly improve and regulate end-game play. For instance, if a game allows players to fight for control of game regions, a map which only has guilds will be one dimensional. Add in trade organizations that may operate across regions and suddenly you have two dimensions with the same players. This in itself is a story, and one that with the right tools can be communicated back out to the players. Using the housing example above, anchoring the ability to build houses to player associations may be a way to organically limit the growth rate of construction in a game. Player groups may be the unit to build (instead of players) and they may only be eligible while the quality of relationships between members remains high enough. Social pressure does the rest. Capture that narrative and push it back out to the affected players and perhaps one or two tiers out (using the same association network). Players would learn about attacks on towns that their friends live in or where their trading partners do business. The game tells a story that people care about. By necessity, this needs to occur in near-real time, a challenge in itself, but done right could absolutely change the face of MMOs today.

Conclusion:

As you can guess, there are a lot of things to consider in anything as complex as a virtual world, so these theories are as much a work in progress as anything else. I hope that they were, at least, somewhat thought provoking. There are plenty of technical limitations preventing much of this from happening in the near future, but adding one new end game system to new MMOs should not be out of the realm of possibility. Hopefully over time some of those will be captured as best practices and replicated out, leaving room for newcomers to add even more dimensions to virtual world game play.

End-Game Primacy: Part 2

If you don’t know how you got here, head back to the Introduction or Part 1. Otherwise, read on:

Part 2: Building the Theory

In a perfect world, developers would just make content all the time to keep players of all kinds entertained by the game world, but that is not possible. Developer resource constraints limit how much content a team can produce in any given amount of time. As a result, there is a natural design triage where teams must choose to implement new features that can most positively impact the game. I have seen people suggest before on forums that this problem can be solved by hiring more programmers, designers, and artists. That is not a real solution because the numbers you would need to hire to eliminate the problem are probably staggering. Further, that many people would bring a host of of organizational issues that would probably impact quality in unintended ways. Given these issues, I am not even considering that avenue an acceptable solution to the problem.

Further, resource constraints are not a problem unique to the gaming industry. In the military, people who didn’t understand the principles were described as “good idea fairies” because their decisions resulted in ineffectual changes that only served to drain resources in time, money, and manpower without actually effectively improving a situation or organization. Unfortunately, the military has been so awash with resources over the past decade, much of this behavior isn’t penalized the way it should be. That is not an option for a gaming business. So I’m going to assume that, at present, the average developer produces content at a mostly fixed rate thanks to effective resource allocation. The way to improve the output of the equation is to find ways to make the content created last longer when faced with players’ content avarice. This is no small feat, given that even veteran game companies sometimes fail to retain players. I cannot claim that it is fool proof, but I think it is possible.

The Theory:

Accepting the reality of resource constraints leads to the first half of end-game primacy: the bulk of any MMO development time should be spent on maximizing end-game content. Most MMOs embrace some form of individual progression system where players consume static content until they finally hit a hard cap on player development. Any content consumed along that progression track essentially comes with an expiration date. It is only consumed for a very small portion of a players overall game experience. In contrast, content at the end-game can be–and is–consumed for much longer, even when it is static. If enough static content exists at the end-game, developers can eventually issue an expansion, pushing the progression wall a little further and starting the cycle over. The most successful games already embrace this half of end-game primacy. Others spend too much time on the initial progression, expecting to have time to expand later only to realize their players did not feel like waiting around. While even this strategy can work, pushing static content to players is still limited. Players still consume it and content themselves with repetition and brand loyalty as the glue that keeps them around long enough to see the next cycle.

Arguably the method of pushing static content is more in line with standard software development practices like object oriented design and agile development. If that was the only way to build content, I think it would be the best way given those advantages, but there is another option. Going back to Ralph Koster‘s quote from Part 1, I want to highlight a particular portion:

You can try a sim-style game which doesn’t supply stories but instead supplies freedom to make them. This is a lot harder and arguably has never been done successfully.

There have been a few attempts at more sim-style content over the past few years, but it is definitely the harder model to do right. That is probably why so many companies choose the safer route. The second half of end-game primacy is that complex systems driven by player interaction provide more longevity than static content. These systems differ from static content in that they allow players to pull content on-demand. An example found in many current games is an auction house. An auction house is always there for players to engage in when they want it. Some players will use it some times, others will use it never, and a rare few will use it as if it is the game itself. It provides a constant stream of content that becomes more dynamic and interesting the more players interact, improving the game play experience for everyone. It can go for years without ever losing player interest, providing maximum impact for developer resources spent. Even if player progression is expanded, the auction house grows with that new bound, while older static content like dungeons generally get left behind.

Limitations:

On paper, dynamic systems like auction houses are superior to static content because they offer players new experiences over longer periods of time. I recognize, however, that they are not all quite so easy to make in practice. Economic models are fairly well developed, so predicting player economic behavior is substantially easier than say, predicting how a player will respond to a powerful monster or even another player. These models make it easier for developers to build tools and mechanisms to govern that behavior (like the auction house) but modeling social behavior is a different animal. Implementing many player versus player systems, for instance, end up being a lot like trying to make a communist economy. It is great in theory, but horrible in practice. There are few games that successfully implement player versus player mechanics and end up with a lot of digital pacifists running around cooperating.

Given these challenges, the end-game systems need to be designed in such a way that they do not cause more harm than good — no small task, to be sure. If this can be accomplished, I feel the amount of development time that these systems entail far outweighs the benefits of spending that same development time creating static content. The initial upfront investment might be higher, but over the long run they end up costing far less in terms of resources. Taking in total, these ideas all left me with the conclusion that bulk of any MMO development time needs to be spent on maximizing end-game content and that this goal is best achieved by embracing complex systems driven by player interaction, rather than static content.

But a principle is only useful if you can make good on it, so in Part 3 I will give a few of my ideas on building meaningful simulations at the end-game of an MMO.

End-Game Primacy: Part 1

Part 1: Exploring Principles:

To suggest that I have a better way to build an MMO is to suggest that there is a problem with the current model. That’s not being entirely fair because there are plenty of good MMOs out there right now. However, it has been my experience as a player that innovation seems to have slowed as more developers choose to replicate the same MMO models across new franchises rather than take big risks of new kinds of MMO game play. My theory is meant to be an alternative, and I hope justification for someone to build this concept. I’m going to start with what I believe needs to be the ultimate goal of any MMO and then work backwards on how I think there is a better way to reach that goal that not only makes a better game for players, but also meets the business needs of developers and producers.

1) Successful MMOs need player volume to make money. Massively multi-player online games are inherently expensive to produce and maintain. From a business model standpoint, this means that the game needs to attract enough players for a long enough period of time to recoup initial development costs, provide future maintenance and development costs, and also make a reasonable profit for the developer and producer. It doesn’t matter if the business model is free to play with micro-transactions or subscription based. A consistent player volume is required for both. This need for money is a hard truth to swallow for those most passionate about these games (myself include) because we tend to idealize the art form. But a healthy player population is not only good for business, it’s also good for game play too (more on that in a moment), which is a goal even the most doe-eyed idealist gamer can get behind.

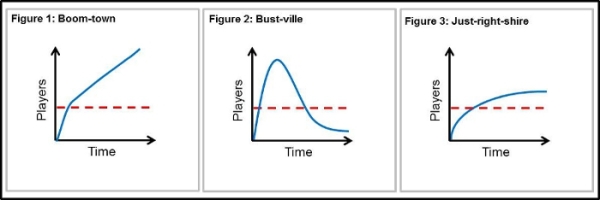

2) A stable population is a function of player retention . To reach the idealized population sweet spot where the game world is bringing in enough money to meet the above objectives, players need to be retained over a period of time. In an ideal world, which I’m going to refer to as “Boom-town” (figure 1), players will opt into the game world and choose to never opt out. This would result in near continuous growth as more and more players try the game. The second scenario, which I’m calling “Bust-ville” (figure 2), shows what happens with many MMOs these days. Players flock to the new game, but their average retention time isn’t long enough to let new players replenish their ranks. The population falls below the theoretical “healthy population” line and fails to make enough money or keep game play interesting enough to attract new players. The last scenario, or “Just-right-shire” (figure 3), is the most realistic goal. The initial spike of players is high enough to get above the healthy population line, and average player retention time is long enough that the population never drops below that line. The game reaches a state of equilibrium or steady sustainable growth.

3) Player retention is tied to content relevant to a players interest. If content is relevant to a players interest, it should theoretically be fun for the player. As long as that content exists, the player should be retained. It sounds simple, but it’s honestly where this gets wildly complicated. Not surprisingly, fun is different for different people. Some players will be attracted to story, others to exploration, others to combat with other players. Most will move back and forth between all of these elements at various times during their retention. There simply is not enough time and resources to make content to appeal to everyone at all times. Even if a game developer decides to focus on appealing to a narrow population group, players consume this content far faster than developers can make it. Consider the quote below from Ralph Koster:

If you write a static story (or indeed include any static element) in your game, everyone in the world will know how it ends in a matter of days. Mathematically, it is not possible for a design team to create stories fast enough to supply everyone playing. This is the traditional approach to this sort of game nonetheless. You can try a sim-style game which doesn’t supply stories but instead supplies freedom to make them. This is a lot harder and arguably has never been done successfully.

Koster is specifically talking about stories, but this holds true for if you substitute any kind of content for stories. Even the most successful MMO development teams today struggle content fast enough to keep their players from consuming it too quickly. At best, they skirt keeping their populations above the healthy line with injections of content as expansions. At worst, they experience Bust-ville, where their initial content release and subsequent content production is too slow to keep player retention up long enough to see population stability. Repetition and pseudo-random elements in the static content can alleviate this somewhat, but these are band-aids to the larger issue. Other variables like brand loyalty or lack of competitors can also extend the life of this content, but they still cannot compete with new content. Even the best roller coaster in the world gets boring after the one hundred forty-seventh time for all but the most extreme roller coaster enthusiasts.

Continue reading more Part 2: Building the Theory or head back to the Introduction to navigate from there.

End-Game Primacy: Introduction

This month’s posts are going to go a bit more abstract and theoretical than the last few I’ve written. This is intentional. While talking about popular upcoming games might draw more traffic to the site, I feel that recently I have not put enough of myself into this blog. I love talking about other games because I love playing them, but those other games were never meant to be the centerpoint (at least not until I’m making them). So today I want to share a working theory I have about how to improve the quality of MMOs today. This theory has developed over time based on reading, personal observation and experience, and many conversations with friends patient enough to listen to me. Here is is up front:

End-game primacy is the idea that the bulk of any MMO development time needs to be spent on maximizing end-game content and that this goal is best achieved by embracing complex systems driven by player interaction, rather than static content. Or put a different way: an MMO’s real story begins after the scripted story ends.

To keep this manageable, I broke my ideas down into three sections. Publishing each part on different days might drive more traffic to the site, but I decided I would rather put this all out at once since it needs to stand together. If you already agree with end-game primacy after reading the short version above, free free to skip to part 3 where I offer some ideas on how to implement it. If you want to see how I came to the theory, go onto part 2. Or if you want to see me talk about some basic concepts related to MMO business models, head to part 1. I hope that this breakdown will also make it easier for people to comment on various sections. Since this is the first time I’m posting this way, please provide feedback if you prefer this format for longer posts. And with that out of the way, I give you my opus:

- Part 1: Exploring Concepts. Development of principles leading up to end-game primacy.

- Part 2: Building the Theory. Construction of the end-game primacy theory.

- Part 3: Squaring the Circle. Ideas on how to build meaningful end-game content.

Til death do us part: Diablo III Hardcore

I spent a fair amount of time playing Diablo III over the past month – along with what I can only imagine is one sixth of the world’s population. Unfortunately, about half of those people have also taken the time to write up detailed reviews of the game. This deluge of commentary left me struggling to find some way to frame my experience with the game that seemed mildly interesting. And then I read a blog discussing death penalities in games that made me realize that Diablo III’s optional permanent-death mode, a.k.a hardcore, was so elegant that it has come to completely redefine what I expected from the game and how I played it.

First, some context: Diablo was my first online game way back over a decade ago. Nostalgia obligates me to play any title in the franchise, even if my tastes in games have moved towards those with persistent worlds. That’s not to say that I wasn’t excited about the game’s release, but more to point out that I expected to play through once or twice to experience the game and then move onto something else. At best, I expected a few weeks of gameplay given that it’s largely an updated and more polished version of what is at it’s core a hack-and-slash dungeon crawler. While some of my friends were keen on pushing through every single difficulty level and were happy to farm demons for gear, I knew that style of gameplay would not hold my attention forever.

Given those expectations, I surprised myself after finishing normal mode by making a new character and selecting hardcore mode. I never played hardcore mode in Diablo II because the idea of investing time in a character only to have them deleted after one death seemed pointless. This time though, the knowledge that I would eventually stop playing the game looming at the front of my mind put the loss of a character into a new context. I realized that the second I stopped playing Diablo III, any character I had invested time in might as well have been deleted anyway. Armed with this realization, I took my new hardcore character – a Wizard – into the now much more dangerous game world. I pushed past normal mode spending every coin, potion, and crafting material I came across knowing that there was no point to holding anything back. If I died, I was dead. About mid-way through Act 1 in nightmare difficulty, I was cut down by a pack of elite spiderlings who cornered me in a cave. My death happened so fast and so unexpectedly, that I was unable to process what had happened. But I experienced neither rage or disappointment; instead, I felt catharsis. The permanent death of my character was somehow more satisfying than actually beating any boss in the game on my normal mode character.

This experience in a game was so unique that I knew I had to try it again. I made several more characters, trying new classes each time to experience the game in a new way. These characters made it to various levels, though never very far due to a bit of recklessness on my part and unfamiliarity with their play styles. I started to become a little frustrated until I noticed that despite each of my characters having to start back at the beginning of the game, my account was still still getting more powerful. My bank and gold carrying over between character deaths started to let me arm and equip my new characters faster. Hardcore purists from Diablo II will argue that this negates some of the challenge, but it was just enough continuity to keep me interested. The game had changed for me.

Despite the simplicity of clicking a mouse over and over, Diablo III’s gameplay at higher difficulties comes down to solving dynamic problems. The game sends new waves of opponents with complex and random abilities and you address these challenges with a finite set of tools. The most powerful of these tools is also the one you appreciate the least until it’s gone: trial and error. If your character cannot truly die, you can brute force your way past some of the more challenging puzzles thrown at you. I love problem solving, but even trying to learn the game’s intricacies, I leaned on the crutch of trial and error when I played through normal difficulty the first time. Hardcore showed me how to get at the good stuff, the uncut version of the game. My most recent hardcore character, a level 51 Witch Doctor, is now in Act I of Hell mode and I absolutely cannot wait to come across the puzzle that finally beats me.

The Diablo III developers have said that it was never intended that hardcore characters would beat the game’s higher difficulties, so it’s unlikely that I will ever “complete” the game. But playing hardcore has artificially extended the game’s life for me. Where some of my friends are already getting bored, I feel like I am just coming into best parts of the game and I do not see an immediate end in sight because I can keep pushing the bar further. Playing hardcore has made me appreciate that sometimes even a simple design on the surface can achieve elegant results and that we gamers have probably taken our digital immortality for granted far too long.

My New Hats

It’s probably about time that I update the Quest. The bad news is I’m finding it harder to keep up posting here regularly. I busted my self-imposed goal of one post a week. Again. The good news is why I’m taking longer to post; I’ve been busy learning for my new job with a fairly young software development company. It turns out that my previous background coupled with the programming and networking courses I started taking a few months ago have made me into an attractive hybrid (except without the tax benefits and lower emissions). The company that hired me doesn’t build games, but the role I’ve been brought on to fill gives me plenty of opportunity to learn about development and work on some of my technical skills. If all you care about is reading about my personal life, you can probably stop here. Anyone else who likes or is curious about games, feel free to keep going.

I wrote last week(ish) about some of my thoughts about the next WoW expansion and its implications on the future of mobile gaming. If you actually made it to the end of the post, you probably noticed I said I was not in the beta. Now I am. This past weekend, I was a part of the 300,000+ annual pass holders who were tossed an invite to the beta. My lovely and talented girlfriend / editor was kind enough to grant me several hours of play time despite my having been away all week on business for my new job. It would be criminal to waste that gift and not share some of my experience in the beta with you all. Spoiler Alert: There are Pandas. Everywhere.

Many of the new features I’m excited to see in the expansion, like pet battles, are not yet implemented on the beta servers. Much of the new class and race content is available, however, and I decided to make the most of it by trying out the games newest class and race: the Pandaren monk.

After making my new character, less-than-cleverly and more-than-hastily named Rollshambo, I logged into the server and was confronted by a sea of black and white fur. It turns out that the other 299,999 invitees also decided to make pandas. While it made the initial experience a little frustrating, I took it in stride and eventually got past some of the early bottleneck and out into the world. I was able to play most of this content at Blizzcon 2011 anyway, so I don’t feel like I missed much by rushing through the area. That is not meant to diminish the content, however. The new quests and objectives are quite amusing, especially when you get to enjoy minor bugs that result in sweet headgear like this.

Online games usually demand teamwork between players to complete objectives, so support roles often end up being simultaneously the most in demand and the least played in the game. Consequently, I usually end up playing one of them. This was my experience playing a healer almost exclusively in World of Warcraft over the past few years. However, doing anything for several years will make anything seem monotonous eventually, so Blizzard’s promise to give the monk a new healing style emphasizing an interactive melee experience piques my interest. I chose the healing specialization, the Mistweaver, at level 10 and worked my way to level 25 over the weekend. While I only have two healing spells by that point, both function differently than almost any other heals I’ve used on other characters, resulting in a unique experience even at this low level of play. Only time and testing will tell if Blizzard can deliver on the hype of the class, but so far I like what I see. In the meantime, I will be enjoying the fact that I have two new hats to wear: novice software developer at work and novice bug “unintended feature” reporter in the Mists of Pandaria beta.

Droids Gone Wild

This week I’m going to spend some time talking about my impressions trying out Star Wars: The Old Republic. As the breakout MMO for BioWare, the game had a lot of hype to live up to given the company’s past performance with several blockbuster franchises such as Mass Effect and Dragon Age. Overall, I found the leveling experience in the Old Republic to be worth the money I shelled out on the game – mostly due to BioWare’s ability to get a player involved in a great story. But I do have some reservations about the game’s ability to draw in long term loyalty from fans. I expect that being tied to the Star Wars franchise itself will keep the game alive for some time, but without streamlined multi-player features, I doubt that I’ll be playing the Old Republic over the long haul. For those with attention issues, I’ve captured my key thoughts below. Everyone else, feel free to hit the text wall at hyper speed.

This week I’m going to spend some time talking about my impressions trying out Star Wars: The Old Republic. As the breakout MMO for BioWare, the game had a lot of hype to live up to given the company’s past performance with several blockbuster franchises such as Mass Effect and Dragon Age. Overall, I found the leveling experience in the Old Republic to be worth the money I shelled out on the game – mostly due to BioWare’s ability to get a player involved in a great story. But I do have some reservations about the game’s ability to draw in long term loyalty from fans. I expect that being tied to the Star Wars franchise itself will keep the game alive for some time, but without streamlined multi-player features, I doubt that I’ll be playing the Old Republic over the long haul. For those with attention issues, I’ve captured my key thoughts below. Everyone else, feel free to hit the text wall at hyper speed.

SWTOR…

… plays like a single player game despite being massively multi-player.

… feels like you’re in a Star Wars movie, to include cross-planet road trips.

… offers some unique gameplay mechanics, despite replicating a lot of WoW’s game design.

… rewards players for their choices, but not necessarily the way you want.

… does a poor job of facilitating group content, a major problem for a multi-player game.

… looks to have a development team who appears to be willing to tackle the game’s weak spots.

Disclaimer: When I started writing this post, I tried not to compare the Old Republic to World of Warcraft because so many others have done it. However, many of the similarities (like the way player skills are grouped) were so obvious that it was like BioWare wanted the familiarity. I’m relatively forgiving of those decisions because who wouldn’t want to copy some of the success of a game with over 10 million subscribers? Where possible, I’ve tried to highlight some of the game’s unique features, many of which do not get much press despite providing substantial portions of the gameplay.

A long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away…

The Old Republic continues BioWare’s track record of emphasizing player-driven story interwoven with gameplay. I find the Star Wars movies entertaining, but I’ve never a diehard fan of the franchise . In spite of my inexperience with the Star Wars universe, playing through the game felt like I was the star in my own prequel movie. Even though I had initially planned to only play a single character, I ended up making and leveling a character in the Republic and the Empire just to see how the plot played out for both sides on various planets. Most MMOs struggle in that every player is a hero, so no one actually feels that way. The Old Republic’s personal stories for each class and the overarching plot woven across all of the planets eliminates that problem by letting each player feel like a real hero.

The visuals in the game contributed heavily to the overall feeling that the story was actually one of the Star Wars movies. Planets, space stations, and abilities alike are aesthetically rendered with details true to the experience at every turn. However, after the initial cool-factor of slicing down enemies with a lightsaber wore off, some of the environmental detail did become a bit much. For example, planets really did start to feel like planets in both detail and physical size around level 25. Even with a speeder at my disposal boosting my travel speed, I often took what can only be described as road trips just to move between quest hubs. Couple that with my compulsive need to leave no stone unturned, and I ended up wasting large amounts of time just traveling. These are forgivable sins for a novice MMO team, but it was a numbing experience and definitely detracted from the overall experience. In total, the graphics of the Old Republic struck a good balance balance between intentionally bright and trying-too-hard-to-be-real-life graphics.

The implementation of a personal crew also went a long way to making the game’s story come to life. Honestly, if I had to pick one feature from the game to take into future games, it would be the crew system. Crew members offset the impact of intentionally compartmentalizing player abilities by giving you the ability to have someone along who can complement your character abilities even when soloing. It dramatically smoothed out some of the edges in the single player experience. Even better, BioWare allows your crew members to craft items, gather resources, and even perform their own missions. This resulted in a similar crafting system available in other games but took the emphasis off of having a player perform repetitive player tasks in favor of simply making scheduling decisions for their crew. I am a huge fan of any system that lets players multi-task and perform some functions away from the keyboard. I hope that the BioWare developers eventually allow players to queue their crew up for multiple back-to-back missions similar to how players could queue skills to learn offline in Eve Online. Coupling your crew to a personal ship even offered BioWare a way to tackle the personal housing in an MMO by giving players their own real estate that does not impact the games static world space. The technique may only work in science fiction games, but this implementation works by giving players a place to call home while still being drawn to major hubs to interact with other players and for other in-game services not available on the ships.

No system is perfect, however, and the story system did have one major wart worth mentioning. BioWare chose to implement an alignment system tied to player choices. Periodically through the course of the plot, player decisions are labeled light or dark. Often these decisions are clear cut, such as letting someone go or killing them, but quite frequently the choices presented to characters are significantly more ambiguous. In previous BioWare games, a character could do what felt right, but in the Old Republic, your light and dark decisions are tied to points which act as a form of currency for some really nice rewards, the best of which can only be purchased if you go to one extreme or the other. This resulted in several situations when my dark-side character had to kill someone to get the dark points I need, even when I wanted to leave a character alive to provide material for future plot. It’s unclear how much of an impact the occasional swap from light to dark would have on a character, but as a player I definitely experienced the pressure to stick with one, ultimately denying some of the choice around which the game is centered. The good news is that BioWare has acknowledged some of the limitations in their initial design and plans to add more rewards for players walking a more neutral path.

Perhaps counter-intuitively, BioWare’s emphasis on personal story in the Old Republic completely turned me off to the game’s multi-player features. For a game that was built and billed as a massively multi-player game, this struck me as a fairly substantial problem looking toward the game’s future. Whenever I tried questing or some of the game scripted content for groups which BioWare has termed “flashpoints,” I became impatient and frustrated that I was not in control of the action anymore. Waiting on my partners to choose dialogue options becomes tedious and my light-side character now carries the title “the Backstabber” because my ally in one of the game’s flashpoints decided to vent some engineers into space to deactivate a security system rather than take an alternate airlock (as I alluded earlier, my rule in these games is never kill someone unless you have to, if for no other reason than that they may offer interesting plot twists later). I ended up leaving many group quests incomplete because the equipment and story rewards in no way justified the time scraping together a group or dealing with problems when group members got out of sync on objectives (this happened often enough for me to get very frustrated several times). As you go up in level, the group options become more numerous as players can choose to participate in warzones, conflict flashpoints (four man adventures) and operations (larger group encounters), but the lack of an effective way to find partners for these features is also going to become an issue as the player base ages and people level characters more sporadically.

BioWare has yet to implement patch 1.2, but the preview appears address some of the features the game seems to sorely lack such as more max level content. One of the most unique features to be added will be the first stage of the game’s legacy system which encourages players to make new characters and level all over again. Leveling up over and over is definitely more compelling in this game than others, and legacy will make it even better, but it will still lose its appeal. So, I still have my reservations as to whether the company will be able to produce content fast enough to keep people occupied. Interestingly however, for the past few months, BioWare had a job vacancy for a social systems designer. The position description included designing unique dynamic content for max level players. The fact that the position is gone now gives me hope that we’ll see more complex design at the end-game in the future.

The Quest

Today’s post is a bit significantly less about game development and the game community, and a bit significantly more about me. If you’ve taken the time to read the About section, you may have seen that I aspire to be a game developer. I’ve undertaken a personal quest to eventually break into the game industry and I’ve decided to chronicle that journey. Periodically, I will make posts like today’s categorized under “The Quest,” which will highlight my progress and hopefully celebrate milestones on the journey, though they may be few and far between since I have a sneaking suspicion that that this is going to be slightly more difficult than killing 10 boars for a little bit of gold and experience.

My educational background is – shall we say – less than ideal for making a transition into the gaming industry. I have yet to see a single job listing for someone with a bachelor’s in history (if anyone reading this finds one – let me know). I’m not without hope, however. While most job listings call for an educational background in computer science, graphic design, web design, networking, public affairs, or marketing, every now and again a very successful developer sneaks into the mix with a much more colorful background. For instance, Greg Street, a lead systems designer for Blizzard Entertainment, has undergraduate degrees in biology and philosophy and a PhD in marine science.

While I don’t have a PhD, my master’s degree in intelligence studies at least has the potential to be as useful as marine science. Being able to do analysis and understand complex problems definitely would be an asset to a game designer. But these are soft skills that can only augment existing knowledge. They don’t stand up well on their own. To that end, I’ve recently enrolled in a local information technology retraining program. I’ve been focusing my time and attention on software development and programming languages. While the course has me working on some programs with more business and commercial applications, I am also working on some simple games.

The current short term goal is that in a few weeks/months you may see some of my early attempts at game development hosted here on the site, and maybe eventually on your own mobile device. We’re still a long way off from that, but there you go – quest accepted.