Archive

Dynamic quest content in 2013: GW2, FFXIV, and WoW

Late last year I wrote a bit about my hopes for dynamic quest content in MMOs. Dynamic quest content was a promise to break away from a fixed linear content model where players are pushed along one or — if you were lucky — a few fixed questing tracks in a game. Once those were complete, players mostly had to wait until new content was released or perform some repetitive tasks, usually in the form of daily quests. This is killer for games whose entire existence is based on a persistent world. Several games have incorporated dynamic content into their play models, so I thought it was worth taking a look back at my experiences with how they implemented this potentially ground-breaking technology.

Guild Wars 2

Guild Wars 2 was the first game to try and incorporate dynamic content. Early on, running around in new zones was exciting. Sure, every now and again you’d run into the same events, but overall it felt like every time you entered a zone, you’d end up having a slightly different gaming experience. That was a huge plus, and I think it ultimately gave the game some good legs for both myself and my wife. The problem was that even though the event chains were extensive, they weren’t random. In fact, they were scripted along relatively narrow paths. And true to form, players found a way to optimize the patterns. I don’t think either of us is entirely sure when the change happened, but over time as players started figuring out patterns in zones and ArenaNet started adding more rewards for dynamic events, doing those events just stopped being fun. The champion farm was born. Masses of players would run in circles around zones knocking off supposedly challenging mobs like they were nothing to get some great rewards. And they can get nasty about it if anyone messes up the cycle. This was particularly bad in low level zones where new players can be exposed to that as some of their first gaming experiences. All the complexity of the dynamic events boiled down into a circuit course with a mob of players that trivialized the encounters.

Guild Wars 2 was the first game to try and incorporate dynamic content. Early on, running around in new zones was exciting. Sure, every now and again you’d run into the same events, but overall it felt like every time you entered a zone, you’d end up having a slightly different gaming experience. That was a huge plus, and I think it ultimately gave the game some good legs for both myself and my wife. The problem was that even though the event chains were extensive, they weren’t random. In fact, they were scripted along relatively narrow paths. And true to form, players found a way to optimize the patterns. I don’t think either of us is entirely sure when the change happened, but over time as players started figuring out patterns in zones and ArenaNet started adding more rewards for dynamic events, doing those events just stopped being fun. The champion farm was born. Masses of players would run in circles around zones knocking off supposedly challenging mobs like they were nothing to get some great rewards. And they can get nasty about it if anyone messes up the cycle. This was particularly bad in low level zones where new players can be exposed to that as some of their first gaming experiences. All the complexity of the dynamic events boiled down into a circuit course with a mob of players that trivialized the encounters.

Final Fantasy XIV: A Realm Reborn

The amazing thing is that even if the model the Guild Wars 2 implemented wasn’t perfect, it’s started to permeate into other MMO contenders. Since I had given Final Fantasy XIV a try when it was first released, I decided to take advantage of my free month. I’d not really followed the games refurbishment, but I was particularly surprised to find out about the FATE system. One of friends told me about the FFXIV’s dynamic quests before I jumped in: “You have your story quests as well that are specific to you and your personal progression through the game, you have class quests for all the different classes, you have FATEs which are basically like guild wars style events, in fact almost EXACTLY the same events in some cases.”

I’m not going to be quite so favorable as to say FFXIVs FATEs were on par with Guild War 2’s dynamic quests, but they definitely had a lot of similarities. Indicators on the mini-map alerted players in the region to crises that demand that players flock from all around. They can last for for up to 15 minutes and have even less impact on the game world. But they did make running around at least slightly more variable. Unlike GW2 dynamic events, however, players are incentivized to participate in FATES thanks to their experience rewards. There were only enough story quests to level your main class so FATE circuits became one of the primary mechanisms for players to level up alternate classes. This was annoying because as with GW2, the events seemed to not scale terribly well past a certain threshold of players. Ultimately, I didn’t play the game for more than a month or so. I can’t say that the FATEs were the single reason, but they definitely didn’t help.

World of Warcraft: Mists of Pandaria

Which brings me to my most current gaming experience with dynamic events: World of Warcraft’s Timeless Isle. I’d stopped played World of Warcraft about a year ago, but the recent announcement for many changes to game in the next expansion at Blizzcon prompted a lot of my old friends to return to the game. We’re going to see if Blizzard’s new “it’s more fun to play with friends” approach to design was as genuine as it seemed listening to them talk about it. To my surprise, I found out that they’d been slowly adopting dynamic event content into their game as well. Thunder Isle in patch 5.3 had a few small dynamic events and the Timeless Isle in patch 5.4 did away completely with scripted daily quests in favor of small little events on the Timeless Isle.

When I first got to the Timeless Isle, I couldn’t help but notice was a few players seemingly running in a circuit. It didn’t take long to figure out that there are a relatively fixed number of possible events and most people just run around looking for them. As with FFXIV and GW2, Blizzard opted to place some small call-outs on the map to alert players to events and rare bosses spawning on the island. Players also tend to call out when then events are up, resulting in mobs of players converging on whatever events happen to be active, just like the champion farms of Guild Wars 2. Overall, there’s a decent range of larger events and smaller events on the island, but the number is so small that it becomes fairly repetitive quickly. Blizzard’s announced there will be more content like this in Warlords of Draenor, so it’ll be interesting to see what they’ve learned and if they can expand on what seems like an growing experiment for the developers.

When I first got to the Timeless Isle, I couldn’t help but notice was a few players seemingly running in a circuit. It didn’t take long to figure out that there are a relatively fixed number of possible events and most people just run around looking for them. As with FFXIV and GW2, Blizzard opted to place some small call-outs on the map to alert players to events and rare bosses spawning on the island. Players also tend to call out when then events are up, resulting in mobs of players converging on whatever events happen to be active, just like the champion farms of Guild Wars 2. Overall, there’s a decent range of larger events and smaller events on the island, but the number is so small that it becomes fairly repetitive quickly. Blizzard’s announced there will be more content like this in Warlords of Draenor, so it’ll be interesting to see what they’ve learned and if they can expand on what seems like an growing experiment for the developers.

Observations

Based on the three games, I’ve come up with a few general observations about what I’d like to see in the next generation of dynamic quest content.

- Most dynamic quests feel “right” for about 2-10 people, beyond that even if monsters scale in health based on the number of players the social dynamic seems to crumble. Announcing the quests to crowded zones tends to draw too many people; it may be worth having several pools of events that can happen in a given zone based on how many people are around (e.g. if a zone is crowded, mostly large scale events designed to accommodate that many occur).

- Cause and effect is still too predictable, and thus exploitable, by the general player base. Most zones seem to have too few events that get cycled through. Logging in results in less of a question of “what will I experience today?” than “when will I experience these events?” It’d be nice if the pool of possible events was large enough and variable enough that you might only see a given event once a week or so.

- Dynamic content can tend to feel disconnected due to the events being somewhat isolated. Responding to individual crisis after individual crisis can feel a bit futile. WoW and Guild Wars have implemented zone wide rewards for participating in certain events in a zone, but these still fall a bit short of a compelling reason why a character is running around after a point. It’d be nice if maybe the game could string a few events together to create individual meta-objectives for players.

- Dynamic content still mostly only impacts the game world locally. In the best implementations, infrastructure and player services can be disrupted, but it’s almost always completely temporary and usually only a minor nuisance. In the worst, the events do absolutely nothing to affect the game. Ideally, it’d be better if a dynamic event affected a wider area. For example, a conflict a few zones over could noticeably affect prices or availability of goods to incentivize players to spread out and also give the world a larger sense of connectivity.

The introduction of dynamic quest content has definitely left a mark on the MMO genre and is becoming a fixture with new, redone, and old games. I’ve not been shy about how excited I am that these games are moving beyond linear content; but I’m also coming to realize that sometimes theory can only take you far. I don’t know yet what the future of dynamic content is going to be in MMOs, but it almost certainly is not yet mature. My hope is that someone can find a way to keep it fresh enough that we can avoid the compulsion to run around in circles waiting for random stimuli. I’d rather wander and be pleasantly surprised, than feel like I’m piling in for the morning commute.

Guild Wars 2: When a map is more than a map

Since the first beta weekend event, I’ve discovered plenty of reasons to love Guild Wars 2. But strangely enough, it’s not the combat or the personal story that has me the most excited after the last stress test. It’s not even world versus world combat. Of all things, it’s the map of Tyria that has my attention. I’m an explorer when it comes to virtual worlds; I like to find their edges. For people like me, the Guild Wars 2 map is more than just a map; it’s a scavenger hunt and a game unto itself.

Each area in Guild Wars 2 has a list of objectives for players to find on every map. Certainly, many of these objectives by themselves are nothing new. Plenty of games award players some kind of recognition for visiting points on a map. But ArenaNet seems to have figured out that overlaying several kinds of objectives with very different reward mechanisms creates a map that demands completion from just about any player. Just as the game’s in-game scouts point out nearby objectives for wayward players, the overall map of Tyria with its tantalizing completion bars encourages players of all kind to get out into the world and explore.

- Hearts of Renown track NPCs you help across the region. Players interested in story or simple level advancement should pursue these to get extra experience not only from the hearts, but the dynamic events they are bound to encounter on the way.

- Waypoints grant every player quick travel capability to point on the map. Having access to these not only improves player quality of life, but makes it easier for players to respond to and participate in rare dynamic events when they pop up.

- Points of Interest may not seem like much, but they offer experience when finding them and any completionist is going to want to hit them all.

- Skill Challenges offer players unique ways to earn skill points outside of normal leveling. Often tucked in out of the way areas, they are a quick way for any player to unlock some utility skills early and gain an edge.

- Vistas are accessible through jumping puzzles. Upon reaching the points, players are rewarded with panoramic cinematics of some of Tyria’s best sites.

- Completing an area awards players with a huge boost of experience as well as a chest with appropriate level gear. These alone make completing a zone worth the extra effort if a player is racing to max level.

Of the objectives described above, vistas are the ones I’ve come to love the most. The jumping puzzles are wonderful diversions from traditional player versus environment game play. They turn the terrain into an opponent. Reaching the vista is sometimes easy with obvious staircases with simple jumps. Sometimes it’s less than intuitive like climbing vines along a wall. Either way, getting the prize is always satisfying. I have never been what you can call a graphics hound when it comes to games, but the cinematic rewards have already created several different backgrounds for my computer and are more than enough reason to seek them out.

At the end of Beta Weekend 3 and the last stress test, there were over 1900 objectives for players to search for in game. This number will only go up as ArenaNet releases new parts of the map to explore in future content updates. Unlike in other games where you can quickly out level an area, minimizing the fun of exploration by taking away the danger, Guild War 2’s dynamic level adjustment keeps every objective relevant for players until each and every one is found. Newly released MMOs are often criticized on release for lacking content, but with such a robust system already tied into the world map, ArenaNet looks well poised to avoid that critique from explorers.

There are two reasons I play MMOs: the experience of playing with others (competitively and cooperatively) and to test the limits and depth of the virtual worlds they provide. The first MMO I played for more than a few months was Asheron’s Call. What got me hooked on that game over other more popular options at the time were the hidden places to explore on the map. I’ve yet to find another MMO with a world quite so robust in terms of exploration potential. With the Guild Wars 2 release date fast approaching, I should soon be able to revise that statement.

Fly or Die – Status of Pet Battles in Mists of Pandaria Beta

One of the best parts about public beta tests is that they let players like me contribute to the game development process. I recently spent a bit of time beta testing the new pet battle system in Mists of Pandaria, the next World of Warcraft expansion. I’ve found that the system is not only a great addition to the game, but also a fairly unique opportunity to study how implementing a theoretical game design can often have unintended consequences. In the current beta build, population imbalance in wild pets creates an environment that heavily favors certain pet families over others. There’s plenty of time for this to change, but unless Blizzard adds a good chunk more wild Dragonkin, Mechanical, and Undead pets to the game, your best bet when the expansion is released is to grab a Flying pet and go to town.

The Mists of Pandaria pet battle system takes its inspiration from Pokemon in that players can assemble teams of pets designed to compete against pets of various types or families. The official site describes this best:

Pets are grouped into common categories called families. Families include Critter, Dragonkin, Mechanical, Magical, and there are many more. Each pet ability also corresponds to a specific pet family; Deep Breath for example is a Dragonkin-type ability, and Lift-Off is a Flying-type ability. Family determines a pet’s strength and weakness against other families. Each family also has a unique passive bonus.

The interaction of pet family strengths and weaknesses adds a strategic layer on what is otherwise a fairly straightforward combat system. On paper, each pet family has comparable strengths and weakness such that no one pet family stands out above the others. In practice on the beta server, however, certain pet families are superior to others because of a disproportionate representation of certain pet families in the wild. For instance, you are 13 times more likely to encounter Critters and 12 times more likely to encounter Beasts than you are to encounter four of the other ten pet families. This population imbalance neuters some bonuses and amplifies some weaknesses to the point of being frustrating while getting your pets to their maximum strength. Bonuses against Critters and Beasts are vastly superior to benefits against other less represented families like Humanoids or Mechanicals.

To be fair, this imbalance is a byproduct of the fact that the existing game had a lot of critters and beasts in various zones. No one can expect Blizzard to radically change the world we’ve come to expect just to account for this. Nevertheless, the current distribution of existing wild pets ends up creating a framework with the following rules of thumb:

- Flying will have a ridiculously easy time leveling.

- Mechanical, Magic, and Beast will have a fairly easy time leveling.

- Dragonkin, Humanoids, Aquatic have a fairly neutral experience.

- Critters will have a fairly difficult time leveling.

- Elemental and Undead will have a ridiculously difficult time leveling.

If you’re interested in how I came up with this, the short version is I weighted every family bonus and weakness using the relative chance of encountering a wild pet of each family type in the current beta build. If you want the longer version with tables and numbers, you can get it here on the Mists of Pandaria feedback forums (I’m Renart). The model does not predict the success of any individual pet — as some pets have multiple damage types — but it does provide a reasonable gauge of overall pet family strength across the whole of the game. Further, a family’s strength will probably vary somewhat due to uneven distribution of the family across the leveling spectrum (e.g. wild Dragonkin only exist at high level). Even with these assumptions taken into account, the above statements are probably still useful guidelines to streamline a player’s pet battle experience and avoid major headaches. Several other testers feel that these observations are consistent with their experiences.

Blizzard has about a month and a half to change the system somehow to alleviate this disparity between families. There are two things I think they could do fairly simply without reworking the whole system. First, converting as many Critter and Beast pets as possible into other less represented families whenever it might make sense would help even out the distribution. This is easiest for pets that already deviate from particular themes (e.g. A Fire Beetle that has fire skills could easily be called an Elemental with Critter skills instead of a Critter with Elemental skills). Second, and perhaps more importantly, adding a good 5-15 additional pets in the Undead, Mechanical, Dragonkin, and Humanoid families would balance out the weakest performing pet families. These two approaches combined would work best. It won’t completely remove the imbalance, but this close to release it seems like a reasonable compromise to mitigate the problem.

I’ve addressed the pet battle system previously to express my belief that it’s probably one of the boldest additions to the MMO ever in that it provides an entirely new content layer across the whole game rather than just expanding the older systems. I still feel that way. But if nothing changes between now and September 25 regarding the conditions I described above, you can bet I’ll be competing with almost everyone trying to catch and train the choice rare Flying pets in game… and probably grabbing a few Magic (+50% damage to Flying) and Mechanical (-33% damage from Flying) ones as well just to handle the inevitable onslaught of moths, buzzards, and parrots we’re all bound to run into.

End-Game Primacy: Part 3

Part 3: Squaring the Circle

If you’re reading this you probably either came straight from the Introduction or were patient enough to work through Part 1 and Part 2. For simplicity, here is the short form of my theory on the ideal MMO content:

End-game primacy is the idea that the bulk of any MMO development time needs to be spent on maximizing end-game content and that this goal is best achieved by embracing complex systems driven by player interaction, rather than static content. Or put a different way: an MMO’s real story begins after the scripted story ends.

As I discussed in part 2, complex systems can be consumed by players longer than static content, but they are also significantly harder to create well. What works in a single player game may not work in an MMO, and vice versa. It is a lot easier to account for a few players’ actions than it is to predict the impact of millions. Millions of players is millions of opportunities to undo any work developers put into the game. Structured static content offers a lot more control for developers. Instancing, phasing, personal stories, and other tools isolate players from the larger game population, while simultaneously making it easier to tell a story to the player. It lets developers preserve the narrative format of single-player games. In contrast, unstructured simulations take control away from a development team. The simulation elements are built into the game world and then left to the players’ whims on what to do with them. This is a frightening prospect because systems not designed to scale particularly well can tend to spiral well out of control, at the detriment of other aspects of the game. For instance, if players can build structures on game landscape, the game world will almost definitely end up suburban. If players can build in a particular spot, they will if for no other reason than they can. Expecting that it would not happen is betting against the odds.

Qualities of Good End-Game Content:

End-game content systems needs to ebb and flow organically, self-regulating through internal feedback mechanisms. In the above example of players building on the terrain, physical game space is limited while the numbers of players who can (and will) build houses has no theoretical limit. Instancing off the construction projects or expanding the physical land mass using some kind of terrain generator are two ways you can address the finite space. I’m not stupid enough to think that the second of those two options is exactly feasible. In many cases, it may be impossible. The alternative of instancing off construction projects or imposing artificial limits on where players can build to control the urban boom misses the point of building a game with lots of players in the first place. To make the system work, there needs to be a natural feedback mechanism in place. For housing, if players can create them – they must also be able to destroy them. Determining the ratio between building and destroying would require a fair amount of find tuning, however. If it’s hard too build and easy too destroy, no one will bother building. On the other hand, if it is to easy to build and to hard to destroy, you still end up with a sprawl.

Going back to Part 2, auction houses have natural self-regulation through the invisible hand of supply / demand, but they lack a mechanism to contribute to player narrative. Systems that have ways to report activity and interactions back out to players are another hallmark of a good end-game system. Players can buy and trade all day on the auction house, but if there is no mechanism to report major fluctuation in trade, players will likely feel isolated in their game experience. Even if such a mechanism exists, it probably does not tie into other systems. Ideally, if a market change occurs, it should be in response to in-game events. Knowledge of these events provides players immersion, rather than just leaving them staring at a user interface spreadsheet tracking their purchases. A good end-game content system will let developers track and aggregate player interactions within and across systems to facilitate narrative development. In the housing example above, a mechanism to monitor and encourage players to cluster buildings together facilitates the construction of towns instead of haphazard sprawl. For instance, perhaps building in close proximity to one another increases their natural defense. Two houses have the defense of three; three the defense of five; and so on. A shack in the woods could be torn down in a few minutes, where several dozen buildings together takes over a day. Several towns merge to form a city which takes a week to siege. And each of these units (e.g. town, city) provides an entity that developers can track and use as a piece to a personal player narrative that is not separate from all other player narratives.

An Opportunity in Player Social Landscape:

These are simplistic examples, to be sure, but it gets to the point of what I’m trying to explain. I cannot suggest an end-game system that will work in every MMO. Each game has its own limitations based on engine, design philosophy, resources and a host of other factors. However, there is one area in many MMOs today that I believe remains underdeveloped, but which also has great potential to add depth to end-game experience and help developers create quality evolving narratives in the process. While most developers spend plenty of time shaping their landscapes and dungeons and are loathe to let players ruin that art, social terrain is an area that does not currently have structure and therefore cannot be destroyed.

The fact that I can often only be the member of one guild and my relationships to other players are defined as “friend” or “not friend” is fairly simplistic. This flat and binary social structure is surprising given that large numbers of players are a feature of MMOs. Certainly, social terrain is difficult to communicate meaningfully – even Facebook struggles with it – but games need more than a few binary associations to link players. In life, we play many roles and in games we do as well. Is there a particular reason that a player can and should only belong to one guild in a game? I would argue no. Further, guilds are generally the only mechanism to permanently join players in games. This is an artificiality that misses the point. Letting players create different kinds of associations among themselves and build on the quality of those relationships through game play would be a fantastic way to add depth to a relatively one dimensional system.

Imagine if player organizations came in many different forms, which were not binding to individual players. Guilds might still exist as the highest form of player grouping, offering resources like shared banks and chat channels. Others might exist for circles of friends to communicate. These circles could extend between guilds and offer benefits like being able to travel immediately to your friends’ location. Still others might exist for trade groups: players who regularly share crafting resources to each others’ benefit. Being a member of this group may offer additional crafting benefits. Player organizations like this only come into existence when the game recognizes a cluster of individual player associations strong enough to warrant it. When players “friend” one another they select the kind of relationship they want to build. Small groups of friendship-linked players might warrant a “friend circle,” clusters of adventuring-linked players might warrant a “guild circle,” and clusters of trade-linked players might warrant a “trade circle,” and so on.

These interlocking social circles would create an inherently organic system that already lies on top of almost any game’s existing game play. Anchoring these circles into less organic game systems could vastly improve and regulate end-game play. For instance, if a game allows players to fight for control of game regions, a map which only has guilds will be one dimensional. Add in trade organizations that may operate across regions and suddenly you have two dimensions with the same players. This in itself is a story, and one that with the right tools can be communicated back out to the players. Using the housing example above, anchoring the ability to build houses to player associations may be a way to organically limit the growth rate of construction in a game. Player groups may be the unit to build (instead of players) and they may only be eligible while the quality of relationships between members remains high enough. Social pressure does the rest. Capture that narrative and push it back out to the affected players and perhaps one or two tiers out (using the same association network). Players would learn about attacks on towns that their friends live in or where their trading partners do business. The game tells a story that people care about. By necessity, this needs to occur in near-real time, a challenge in itself, but done right could absolutely change the face of MMOs today.

Conclusion:

As you can guess, there are a lot of things to consider in anything as complex as a virtual world, so these theories are as much a work in progress as anything else. I hope that they were, at least, somewhat thought provoking. There are plenty of technical limitations preventing much of this from happening in the near future, but adding one new end game system to new MMOs should not be out of the realm of possibility. Hopefully over time some of those will be captured as best practices and replicated out, leaving room for newcomers to add even more dimensions to virtual world game play.

End-Game Primacy: Part 2

If you don’t know how you got here, head back to the Introduction or Part 1. Otherwise, read on:

Part 2: Building the Theory

In a perfect world, developers would just make content all the time to keep players of all kinds entertained by the game world, but that is not possible. Developer resource constraints limit how much content a team can produce in any given amount of time. As a result, there is a natural design triage where teams must choose to implement new features that can most positively impact the game. I have seen people suggest before on forums that this problem can be solved by hiring more programmers, designers, and artists. That is not a real solution because the numbers you would need to hire to eliminate the problem are probably staggering. Further, that many people would bring a host of of organizational issues that would probably impact quality in unintended ways. Given these issues, I am not even considering that avenue an acceptable solution to the problem.

Further, resource constraints are not a problem unique to the gaming industry. In the military, people who didn’t understand the principles were described as “good idea fairies” because their decisions resulted in ineffectual changes that only served to drain resources in time, money, and manpower without actually effectively improving a situation or organization. Unfortunately, the military has been so awash with resources over the past decade, much of this behavior isn’t penalized the way it should be. That is not an option for a gaming business. So I’m going to assume that, at present, the average developer produces content at a mostly fixed rate thanks to effective resource allocation. The way to improve the output of the equation is to find ways to make the content created last longer when faced with players’ content avarice. This is no small feat, given that even veteran game companies sometimes fail to retain players. I cannot claim that it is fool proof, but I think it is possible.

The Theory:

Accepting the reality of resource constraints leads to the first half of end-game primacy: the bulk of any MMO development time should be spent on maximizing end-game content. Most MMOs embrace some form of individual progression system where players consume static content until they finally hit a hard cap on player development. Any content consumed along that progression track essentially comes with an expiration date. It is only consumed for a very small portion of a players overall game experience. In contrast, content at the end-game can be–and is–consumed for much longer, even when it is static. If enough static content exists at the end-game, developers can eventually issue an expansion, pushing the progression wall a little further and starting the cycle over. The most successful games already embrace this half of end-game primacy. Others spend too much time on the initial progression, expecting to have time to expand later only to realize their players did not feel like waiting around. While even this strategy can work, pushing static content to players is still limited. Players still consume it and content themselves with repetition and brand loyalty as the glue that keeps them around long enough to see the next cycle.

Arguably the method of pushing static content is more in line with standard software development practices like object oriented design and agile development. If that was the only way to build content, I think it would be the best way given those advantages, but there is another option. Going back to Ralph Koster‘s quote from Part 1, I want to highlight a particular portion:

You can try a sim-style game which doesn’t supply stories but instead supplies freedom to make them. This is a lot harder and arguably has never been done successfully.

There have been a few attempts at more sim-style content over the past few years, but it is definitely the harder model to do right. That is probably why so many companies choose the safer route. The second half of end-game primacy is that complex systems driven by player interaction provide more longevity than static content. These systems differ from static content in that they allow players to pull content on-demand. An example found in many current games is an auction house. An auction house is always there for players to engage in when they want it. Some players will use it some times, others will use it never, and a rare few will use it as if it is the game itself. It provides a constant stream of content that becomes more dynamic and interesting the more players interact, improving the game play experience for everyone. It can go for years without ever losing player interest, providing maximum impact for developer resources spent. Even if player progression is expanded, the auction house grows with that new bound, while older static content like dungeons generally get left behind.

Limitations:

On paper, dynamic systems like auction houses are superior to static content because they offer players new experiences over longer periods of time. I recognize, however, that they are not all quite so easy to make in practice. Economic models are fairly well developed, so predicting player economic behavior is substantially easier than say, predicting how a player will respond to a powerful monster or even another player. These models make it easier for developers to build tools and mechanisms to govern that behavior (like the auction house) but modeling social behavior is a different animal. Implementing many player versus player systems, for instance, end up being a lot like trying to make a communist economy. It is great in theory, but horrible in practice. There are few games that successfully implement player versus player mechanics and end up with a lot of digital pacifists running around cooperating.

Given these challenges, the end-game systems need to be designed in such a way that they do not cause more harm than good — no small task, to be sure. If this can be accomplished, I feel the amount of development time that these systems entail far outweighs the benefits of spending that same development time creating static content. The initial upfront investment might be higher, but over the long run they end up costing far less in terms of resources. Taking in total, these ideas all left me with the conclusion that bulk of any MMO development time needs to be spent on maximizing end-game content and that this goal is best achieved by embracing complex systems driven by player interaction, rather than static content.

But a principle is only useful if you can make good on it, so in Part 3 I will give a few of my ideas on building meaningful simulations at the end-game of an MMO.

End-Game Primacy: Part 1

Part 1: Exploring Principles:

To suggest that I have a better way to build an MMO is to suggest that there is a problem with the current model. That’s not being entirely fair because there are plenty of good MMOs out there right now. However, it has been my experience as a player that innovation seems to have slowed as more developers choose to replicate the same MMO models across new franchises rather than take big risks of new kinds of MMO game play. My theory is meant to be an alternative, and I hope justification for someone to build this concept. I’m going to start with what I believe needs to be the ultimate goal of any MMO and then work backwards on how I think there is a better way to reach that goal that not only makes a better game for players, but also meets the business needs of developers and producers.

1) Successful MMOs need player volume to make money. Massively multi-player online games are inherently expensive to produce and maintain. From a business model standpoint, this means that the game needs to attract enough players for a long enough period of time to recoup initial development costs, provide future maintenance and development costs, and also make a reasonable profit for the developer and producer. It doesn’t matter if the business model is free to play with micro-transactions or subscription based. A consistent player volume is required for both. This need for money is a hard truth to swallow for those most passionate about these games (myself include) because we tend to idealize the art form. But a healthy player population is not only good for business, it’s also good for game play too (more on that in a moment), which is a goal even the most doe-eyed idealist gamer can get behind.

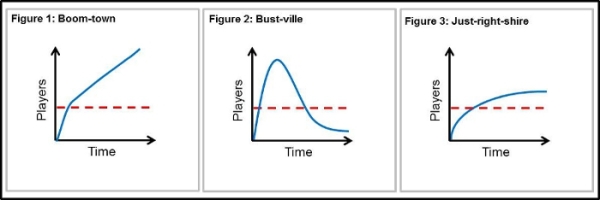

2) A stable population is a function of player retention . To reach the idealized population sweet spot where the game world is bringing in enough money to meet the above objectives, players need to be retained over a period of time. In an ideal world, which I’m going to refer to as “Boom-town” (figure 1), players will opt into the game world and choose to never opt out. This would result in near continuous growth as more and more players try the game. The second scenario, which I’m calling “Bust-ville” (figure 2), shows what happens with many MMOs these days. Players flock to the new game, but their average retention time isn’t long enough to let new players replenish their ranks. The population falls below the theoretical “healthy population” line and fails to make enough money or keep game play interesting enough to attract new players. The last scenario, or “Just-right-shire” (figure 3), is the most realistic goal. The initial spike of players is high enough to get above the healthy population line, and average player retention time is long enough that the population never drops below that line. The game reaches a state of equilibrium or steady sustainable growth.

3) Player retention is tied to content relevant to a players interest. If content is relevant to a players interest, it should theoretically be fun for the player. As long as that content exists, the player should be retained. It sounds simple, but it’s honestly where this gets wildly complicated. Not surprisingly, fun is different for different people. Some players will be attracted to story, others to exploration, others to combat with other players. Most will move back and forth between all of these elements at various times during their retention. There simply is not enough time and resources to make content to appeal to everyone at all times. Even if a game developer decides to focus on appealing to a narrow population group, players consume this content far faster than developers can make it. Consider the quote below from Ralph Koster:

If you write a static story (or indeed include any static element) in your game, everyone in the world will know how it ends in a matter of days. Mathematically, it is not possible for a design team to create stories fast enough to supply everyone playing. This is the traditional approach to this sort of game nonetheless. You can try a sim-style game which doesn’t supply stories but instead supplies freedom to make them. This is a lot harder and arguably has never been done successfully.

Koster is specifically talking about stories, but this holds true for if you substitute any kind of content for stories. Even the most successful MMO development teams today struggle content fast enough to keep their players from consuming it too quickly. At best, they skirt keeping their populations above the healthy line with injections of content as expansions. At worst, they experience Bust-ville, where their initial content release and subsequent content production is too slow to keep player retention up long enough to see population stability. Repetition and pseudo-random elements in the static content can alleviate this somewhat, but these are band-aids to the larger issue. Other variables like brand loyalty or lack of competitors can also extend the life of this content, but they still cannot compete with new content. Even the best roller coaster in the world gets boring after the one hundred forty-seventh time for all but the most extreme roller coaster enthusiasts.

Continue reading more Part 2: Building the Theory or head back to the Introduction to navigate from there.

End-Game Primacy: Introduction

This month’s posts are going to go a bit more abstract and theoretical than the last few I’ve written. This is intentional. While talking about popular upcoming games might draw more traffic to the site, I feel that recently I have not put enough of myself into this blog. I love talking about other games because I love playing them, but those other games were never meant to be the centerpoint (at least not until I’m making them). So today I want to share a working theory I have about how to improve the quality of MMOs today. This theory has developed over time based on reading, personal observation and experience, and many conversations with friends patient enough to listen to me. Here is is up front:

End-game primacy is the idea that the bulk of any MMO development time needs to be spent on maximizing end-game content and that this goal is best achieved by embracing complex systems driven by player interaction, rather than static content. Or put a different way: an MMO’s real story begins after the scripted story ends.

To keep this manageable, I broke my ideas down into three sections. Publishing each part on different days might drive more traffic to the site, but I decided I would rather put this all out at once since it needs to stand together. If you already agree with end-game primacy after reading the short version above, free free to skip to part 3 where I offer some ideas on how to implement it. If you want to see how I came to the theory, go onto part 2. Or if you want to see me talk about some basic concepts related to MMO business models, head to part 1. I hope that this breakdown will also make it easier for people to comment on various sections. Since this is the first time I’m posting this way, please provide feedback if you prefer this format for longer posts. And with that out of the way, I give you my opus:

- Part 1: Exploring Concepts. Development of principles leading up to end-game primacy.

- Part 2: Building the Theory. Construction of the end-game primacy theory.

- Part 3: Squaring the Circle. Ideas on how to build meaningful end-game content.

The Elder Scroll of Speculation

Game Informer today confirmed the not-so-secret existence of an an already-in-development Elder Scrolls Online MMO. Porting the highly successful single-player Elder Scrolls franchise to a massively-multiplayer environment is a high risk, high reward move for ZeniMax Studios. On one hand, already having a huge fan base to draw on means that the studio can count on a fair amount of revenue up front on release as long as they deliver a working game. On the other hand, those same fans are going to demand the kind of game experience that they’ve come to expect from other games in the franchise: a rich open world where players decide how they want to play. Translating that single-player experience into a multi-player environment may not be simple, so ZeniMax will have to come up with some fairly creative solutions to bring the Elder Scrolls alive in a way that mediates the demands of the MMO genre with expectations of their players.

While ZeniMax probably won’t give away too many details about specific game mechanics this far out from release, we can probably expect to hear soon about overarching design concepts and major game features. When Game Informer releases an exclusive trailer tomorrow, my biggest fear is that we’ll see a game that resembles another attempt to piggy-back off World of Warcraft. While this approach has arguably worked for some MMO franchises (e.g. Rift and SWTOR), it also tends to draw a lot of criticism from MMO players and probably cut hard into those franchises’s potential growth than if they’d tried a different approach. Don’t get me wrong, WoW is a great game even seven years after release – but if I want to play it, I’ll play Blizzard’s version and I believe many other players feel the same way. Blizzard had seven years to flesh out what is, at its core, a very structured MMO experience. Even a great emulation of that style of game play, especially without those seven extra years of development, is probably going to pale in comparison to precedent set by the open worlds of previous Elder Scrolls game.

Tomorrow, if we’re comparing ZeniMax’s Elder Scrolls MMO to any other game on the market, I hope we’re talking about EVE Online. While I do not want ZeniMax to copy EVE wholesale, for many of the same reasons I do not want want them to copy WoW, there are definitely lessons to be learned and some features which may be too useful to pass up when moving Tamriel to the internet. EVE is probably the best implementation of a massive open online world where players can have direct impact on the world itself. Instead of picking classes as in other more structured MMOs, EVE’s players choose how to develop their character using an expansive skill-tree system. They can specialize or diversify across skills that impact various aspects of the game’s social, economic, and combat systems, gaining more depth the longer they play. This flexibility in game play and character development are the same reasons why everyone I know enjoyed Skyrim. As the last Elder Scrolls game to be released, players will almost definitely expect similar flexibility in the Elder Scrolls Online.

Tomorrow, if we’re comparing ZeniMax’s Elder Scrolls MMO to any other game on the market, I hope we’re talking about EVE Online. While I do not want ZeniMax to copy EVE wholesale, for many of the same reasons I do not want want them to copy WoW, there are definitely lessons to be learned and some features which may be too useful to pass up when moving Tamriel to the internet. EVE is probably the best implementation of a massive open online world where players can have direct impact on the world itself. Instead of picking classes as in other more structured MMOs, EVE’s players choose how to develop their character using an expansive skill-tree system. They can specialize or diversify across skills that impact various aspects of the game’s social, economic, and combat systems, gaining more depth the longer they play. This flexibility in game play and character development are the same reasons why everyone I know enjoyed Skyrim. As the last Elder Scrolls game to be released, players will almost definitely expect similar flexibility in the Elder Scrolls Online.

As I said earlier, what works in a single player game may not work in an MMO, but the reverse is also true. Trying to give players an open world like EVE’s without losing the richness of content and story is a challenge in itself. It’s a lot easier to account for one player’s actions in a game world than it is for thousands, and if it’s a true open world, that’s thousands of opportunities for players to undo any work developers put into the game. Game Informer’s tease about The Elder Scrolls says that ZeniMax has already decided structure the player versus player aspect the game with three set factions. This design is not entirely surprising given that ZeniMax’s president used to work on Dark Ages of Camelot, which also featured a three-faction PvP system. It remains to be seen, however, if the studio will cede more freedom to players in other aspects of the Elder Scrolls Online experience.

If nothing else, the next year will be interesting to see how ZeniMax chooses to balance these competing forces.

Legends have to learn to make choices like this.

Despite a few not entirely unexpected hiccups related to the sheer volume of players, Guild Wars 2 turned out to be surprisingly “finished” for a beta, especially since only three of the five player races were available for play testing. Trying to play the beta ended up being a lot like trying to eat responsibly at a buffet restaurant; I tried to stick to a few things I knew I’d want to play, but ended up trying almost everything once I saw how good it all looked. I had such a blast giving this game a test-drive that I actually forgot to take screen shots of many areas I’d intended to document. This lack of some of the best eye candy will truly be to your disadvantage because the game’s graphics and cut scenes are both high-quality and have a very unique style.

I could probably go on for pages giving play by plays of the major game features, but I think other gaming news sites have already covered that pretty well. Instead I’d like to share my overall impression of the game’s design and what made it stand out for me when compared against games I’ve played at this stage in development. For those who like lists:

Guild Wars 2…

- … is heavy on interesting choices.

- … offers an incredibly fluid gaming experience.

- … has dynamic content that had me participating instead of grinding.

And now on with the show.

Guild Wars 2 is heavy on interesting choices.

Virtually every aspect of Guild Wars 2 is filled with choices. These choices aren’t the run-of-the-mill decisions like “would you like +1 damage or +1 health” or “would you like fries with that?”, but rather fairly compelling and interesting choices like this one:

Some of the first interesting choices I was hit with came right at the beginning with character creation. In addition to the usual choice of race, class, and physical appearance, I was able to customize the look and feel of my armor right out the gate. More importantly, I was presented with a number of short anecdotes about my background to choose from, like what I did at a recent party, which god / nature spirit blessed me as a child, or if I grew up on the streets or in a noble family. Upon finishing the character, I was launched into a short video detailing my character’s past and current situation, influenced by the story choices I made during creation. This was a nice touch that signaled immediately that the decisions made at the character screen weren’t just cosmetic and would color the game play experience.

Choices don’t just have to do with story, however. All characters’ main combat abilities are governed by a combination of their equipped weapons and their profession, or class as other games usually call them. Equipping different weapons gave me five completely different primary attacks and each profession also has a secondary mechanic which changed up the skill dynamic to offer flexibility. For instance, an Elementalist can’t change weapons while fighting, but can swap between the four elements (fire, water, earth, or air) mid-battle to radically change the style of combat currently being used despite what weapon you have equipped. An Elementalist using a staff will have five different fire skills than one wielding a sword, and two Elementalists wielding staves may have different abilities at any given time depending on if they are using the same element or not. This flexibility was what lead me to try out the Elementalist profession first, but it wasn’t long until I saw other characters using awesome ability combinations and I felt compelled to try a few more professions. I ended up trying the Necromancer and Thief as well, but spent the lion’s share of my time as the Engineer, a gun-totting adventurer with a steampunk inspired arsenal literally on his back.

The complexity that weapon and profession skills brought to the combat system let me make non-binding game-play choices early on that really impacted my personal combat style. Combine that with the fact that each profession has a few dozen utility abilities, but can only use four at a time, and I ended up really thinking hard about what weapon and utility abilities I equipped to tackle different situations. To be fair, this much flexibility does include some risk that you can temporarily invest in the “wrong” skills, but it’s a fairly marginal risk in that a mistake doesn’t last long. For instance, I added skill points to some grenades on my engineer that I thought might be interesting, only to find they didn’t support my current play style. I wasn’t able to find a way to respend those points, but it wasn’t too long before I had enough points to get a new skill to replace it. Further, it looks like at max level you’ll have all the utility abilities anyway. It probably wouldn’t hurt if they added a mechanic to let players redo those points, however, especially since there are already books that let you reset your talents (mostly passive boosts to one facet of your character).

Guild Wars 2 offers an incredibly fluid gaming experience.

The ArenaNet team has not only accomplished building a game that offers interesting choices at its core and periphery, but also managed to keep a lot of subtler features that tend to fall by the wayside in other games. These immersive features let me flow between aspects of the game both from a story perspective and also in terms of teaching me to handle the necessary evils of learning to perform my role via the game’s interface. They mitigated what could have been a paralyzing game experience in such a big world into something much more enjoyable. Nothing is more frustrating than not really knowing what to do next and retreading ground as you end up trying to figure out where to go.

One of the features that I hadn’t really seen discussed anywhere else, but which I found very ingenious, were the in-game scouts. Friendly NPCs marked on the minimap with a spyglass were usually hanging around natural junctions between areas in the game. These scouts would pull up my world map and give me a little briefing on the local area, highlighting with a “pen” where I could find things to do in the area. It’s a relatively minor feature for players who are familiar with a region already, but it’s very thoughtful toward new players by giving them a little help getting around without outright handing a complete map of the game to everyone, ruining it for those who like to explore (like me).

Actual underwater combat is another arguably unnecessary, but completely awesome and fluid (pun intended), feature in Guild Wars 2. Fighting underwater is usually a niche experience in many games, to the point that some don’t even allow you to swim and those that do usually restrict it to fairly marginal areas. When supported, underwater combat is usually identical to land based combat, but you move a lot slower, in three dimensions, and may or may not have to pay attention to a “breath” meter. In comparison, the Guild Wars aquatic experiences are seamlessly integrated throughout the story experience. There are hidden objectives under lakes in new player areas and about one quest in ten quest areas involves some kind of water component. Immediately going underwater shifts you to your aquatic weapon, which as noted in the section about choices, switches you directly to a new set of five abilities. Other above-ground utility abilities have new and improved functions when underwater. On my engineer, I had an ability to shoot an oil slick out behind me on dry land to slow people chasing me… that oil slick became cloud of oil that blinded opponents underwater.

Really everything just moved in the game. It just felt natural to move from area to area, from quest to quest, from event to event, from story to story, and from every facet of the game to every other facet of the game. Lately it seems like many MMO developers forgot to take notes about what people hate about the genre, but that was clearly not the case with the ArenaNet development team.

Guild Wars 2 has dynamic content that had me participating instead of grinding.

As I went on in great length in my previous post, the Guild Wars 2 dynamic event system was the number one feature I wanted to test out this weekend. Luckily, the ArenaNet team did not let me down on this one. I can honestly say that the most fun I had during the weekend was when a random event would occur near where I was doing other things and then an hour later I’d realize that the events had literally pulled me along for the ride.

I’d be lying if I said I wasn’t a bit worried at first. The first dynamic events you experience at low levels are directly scripted into the encounters or seem to occur on a periodic loop where a single event affects a particular area at somewhat predictable intervals. These events, while epic and unexpected the first time around, are by their very nature not dynamic. Truthfully, I was worried that this would carry over as I progressed, but I think this is more of the ArenaNet team’s way of easing players into what can be a somewhat unpredictable experience later on.

It didn’t take long, though, to find the dynamic experience what I was waiting for. Around level 10 or so on my Engineer, I was making my way to a town when all of a sudden a fort nearby came under attack by a band of centaurs. The game let me know immediately I was in range to assist and as I did not see many others around, I went to assist. One other brave defender and I failed to fight the horde of centaurs off and they took over the fort. It was the first event I’d seen fail, and I couldn’t have been happier. A few minutes later, a new event appeared to retake the fort. More people gathered; we retook the fort and were ushered out to several new objectives. Nearby farms needed repairs from the raid and we had to retrieve citizens taken captive during the centaur attack. Liberating those citizens turned into a counter attack at the centaur forward garrison. I literally spent two hours just following the flow of events as the story unfolded.

While it does seem like this event will probably repeat itself eventually if the centaurs are not contained, the overall chain was both well thought out and, most importantly, fun to experience so early in a game. As I played through the world with other characters, I found that being the same areas at different times can often result in an entirely different chain and that ignoring events for too long does have an impact on the game world. On my Skarr Thief, I came across a few way points (quick travel and resurrection areas) that were contested as a result of events. Players had to work to take those areas back, but the minor inconvenience of getting it back was completely worth the fun of actually doing it. To add icing to the already awesome cake, just playing the centaur events I described above gave my Engineer a full level of experience both from the event itself and because events usually tie in directly with activities you’re doing while you’re in an area. I don’t know exactly what metric is uses to grade your performance, but at the end of each I got a bronze, silver, or gold medal with appropriately scaled experience rewards and other rewards. The grading metric seems smart enough to not just look at how much damage you do, as sometimes I’d get a gold medal just for helping a few downed players.

Keeping in mind that I only saw 2 days worth of low level content, the one criticism I have of dynamic events so far is that while events do impact the world, they almost impact the world too quickly. Failing or succeeding an event could occur in about 10 minutes, resulting in quick changes to a local area. For instance, the campaign against the centaur horde progressed from just outside the gate to its complete suppression in only about 30 minutes. This may be a byproduct of the massive number of low level players around, so it may not matter much as the game gets more mature, but I figure it’s worth mentioning.

One small side-note on dynamic events: PvP is dynamic by its very nature, but the ArenaNet team has also worked in some extra dynamism into their world versus world combat. I ended up only doing about two hours of PvP combat, but the short bit I did play was in the world versus world area. Each server battled for control of a fairly expansive region… but these weren’t just static keeps to trade hands. Keeping a fortress ended up requiring supplies and those supplies were sent via dynamic caravans that would move between forts and keeps a particular side would control. A friend of mine and I had a blast hunting those caravans down and taking them out.

Overall…

I’m incredibly pleased with the experience I had during the Open Beta Weekend. Like a good movie trailer, I felt like I saw enough to get excited without worrying that I had seen too much too ruin the whole thing. The thoughtful designs put into this game are sure to make it a hit among the MMO community and I wouldn’t be surprised if other developers start emulating some of the great mechanics woven into Guild Wars 2. This was a pretty long post as is, but if anyone has additional questions about specific parts of the game, I would be more than happy to share what I can on those topics in the comments.

My New Hats

It’s probably about time that I update the Quest. The bad news is I’m finding it harder to keep up posting here regularly. I busted my self-imposed goal of one post a week. Again. The good news is why I’m taking longer to post; I’ve been busy learning for my new job with a fairly young software development company. It turns out that my previous background coupled with the programming and networking courses I started taking a few months ago have made me into an attractive hybrid (except without the tax benefits and lower emissions). The company that hired me doesn’t build games, but the role I’ve been brought on to fill gives me plenty of opportunity to learn about development and work on some of my technical skills. If all you care about is reading about my personal life, you can probably stop here. Anyone else who likes or is curious about games, feel free to keep going.

I wrote last week(ish) about some of my thoughts about the next WoW expansion and its implications on the future of mobile gaming. If you actually made it to the end of the post, you probably noticed I said I was not in the beta. Now I am. This past weekend, I was a part of the 300,000+ annual pass holders who were tossed an invite to the beta. My lovely and talented girlfriend / editor was kind enough to grant me several hours of play time despite my having been away all week on business for my new job. It would be criminal to waste that gift and not share some of my experience in the beta with you all. Spoiler Alert: There are Pandas. Everywhere.

Many of the new features I’m excited to see in the expansion, like pet battles, are not yet implemented on the beta servers. Much of the new class and race content is available, however, and I decided to make the most of it by trying out the games newest class and race: the Pandaren monk.

After making my new character, less-than-cleverly and more-than-hastily named Rollshambo, I logged into the server and was confronted by a sea of black and white fur. It turns out that the other 299,999 invitees also decided to make pandas. While it made the initial experience a little frustrating, I took it in stride and eventually got past some of the early bottleneck and out into the world. I was able to play most of this content at Blizzcon 2011 anyway, so I don’t feel like I missed much by rushing through the area. That is not meant to diminish the content, however. The new quests and objectives are quite amusing, especially when you get to enjoy minor bugs that result in sweet headgear like this.

Online games usually demand teamwork between players to complete objectives, so support roles often end up being simultaneously the most in demand and the least played in the game. Consequently, I usually end up playing one of them. This was my experience playing a healer almost exclusively in World of Warcraft over the past few years. However, doing anything for several years will make anything seem monotonous eventually, so Blizzard’s promise to give the monk a new healing style emphasizing an interactive melee experience piques my interest. I chose the healing specialization, the Mistweaver, at level 10 and worked my way to level 25 over the weekend. While I only have two healing spells by that point, both function differently than almost any other heals I’ve used on other characters, resulting in a unique experience even at this low level of play. Only time and testing will tell if Blizzard can deliver on the hype of the class, but so far I like what I see. In the meantime, I will be enjoying the fact that I have two new hats to wear: novice software developer at work and novice bug “unintended feature” reporter in the Mists of Pandaria beta.